Paying it forward

Feature

Attitudes towards environmental sustainability across the economy have shifted dramatically in recent years. Consumers1 are demanding sustainable products and services—even if that comes at a premium—and are willing to vote with their feet when businesses fail to deliver. Governments all over the world are not only incentivizing sustainable corporate practices, but introducing regulations that mandate it. Investors, too, are increasingly reviewing their positions in light of sustainability commitments. As the world strives for net zero—where greenhouse gasses removed from the atmosphere are equal to the amount emitted—corporations not only face an ethical obligation but a business imperative. Any organization that wants to attract top talent, compete at full tilt, or shore up their customer base—fundamentally any business that wants to survive and thrive—can view it net zero as an opportunity.

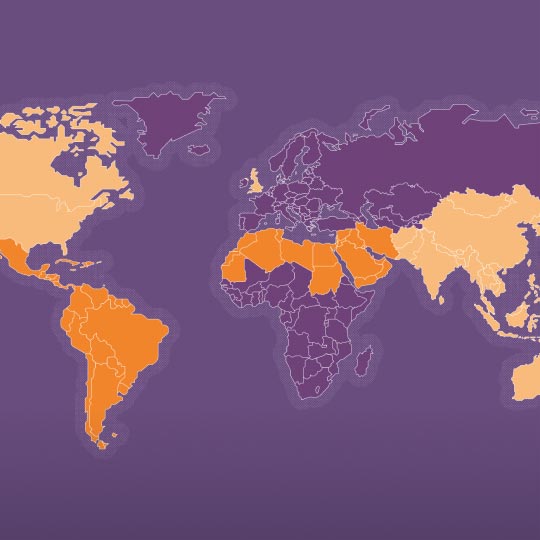

Payments businesses are no exception. Expected to realize $3 trillion in revenues2 by 2027, the sector operates at vast scale. When it comes to reducing and managing the carbon costs of its operations, it is subject to the same expectations as any other major industry. But it is also in the unusual position of being part of all other industries, too. Payments companies can help those other sectors realize their own ambitious ESG environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals, in turn growing payments revenues through sustainability-focused products and services.

The question is: What precisely are the sustainability opportunities for payments companies? Here, we examine three key areas where environmentally-focused innovation is taking place, and consider what lies ahead...

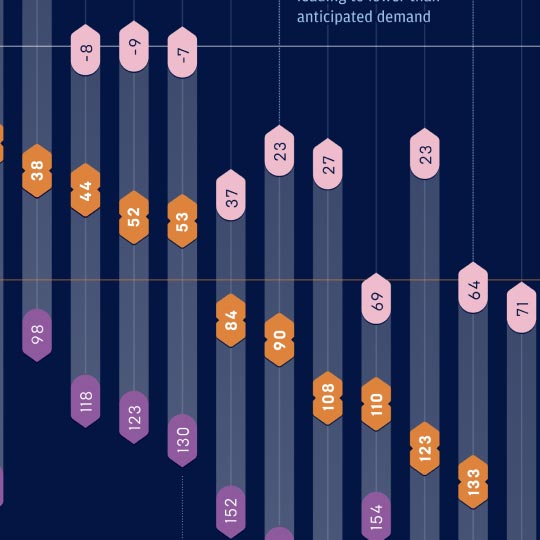

Cash is now used in fewer than one in five3 purchases, and electronic payments are surging. Digital wallets are expected to account for 46 percent4 of point-of-sale spending by 2027, up from 30 percent in 2023. As the digital payments ecosystem grows, so does the sheer volume of computation required to power all of the transactions. In 2023, 724 billion5 electronic transactions were processed via credit cards.

Data centers play a critical role in the associated processing, storage and analytics, and they can have a significant carbon footprint. It’s not only powering the machines that is energy-intensive but also the need to keep them cool—running a data center at hot temperatures can imperil the equipment. An individual payment is estimated to represent 3.78 grams6 of CO2, which can collectively amount to a million tons7 of CO2 per year emitted in the United Kingdom alone. Payments companies are also exploring how generative AI can augment their own processes, operations and services—but the models on which generative AI depends consume massive amounts of energy, 33 times8 more than task-specific software. “The world, in general, has a growing demand for energy,” explains Tristan Attenborough, Global Head of Energy, Power, Renewables, Metals and Mining at J.P. Morgan Payments. “The data center impacts of AI are going to vastly increase that demand.”

So how can the payments sector reduce its energy burden? One strategy is simply to opt where possible for more energy-efficient hardware. Data centers can run off renewable sources of energy; one geothermal power project9 in Nevada, USA, provides 3.5 megawatts of energy to a major tech company’s facility. In Sweden, a data center operator is investigating building a small nuclear reactor10 to power one of its facilities. If a payments company is building a private data center, or partnering with a technology company for cloud or AI services, they can seek out these kinds of innovations.

A more subtle strategy, however, is to reinvent payment processes themselves. Each card transaction involves a number of intermediaries, from the card issuer through to the merchant’s bank. “Moving data from one step to another in this complex back-end process generates carbon emissions,” explains Lena Tailor, VP of Partnering, Talent and Inclusion at GoCardless, a payment provider specializing in direct bank payments.

It’s one reason why interest in these types of transactions, also known as account-to-account (A2A) payments, is growing. This is good news for the environment. “A2A payments are much less carbon intensive because there are fewer intermediaries,” says Tailor, who states that an A2A payment generates roughly four times fewer emissions than a card payment.

Paying for something with a bank transfer is nothing new, but developments in open banking are driving even more growth of A2A payments. Open banking has been growing in the United Kingdom and continental Europe since legislation supporting it came into force in 2018. Broadly speaking, open banking entails using application programming interfaces (APIs) to connect accounts to third-party financial services. Open-banking enabled A2A payments volumes are expected to exceed $330 billion by 202711, compared to $57 billion in 2023. Another environmental consideration relating to A2A payments is they don’t involve physical payment cards. Payment cards are generally made from polyvinyl chloride, a plastic which is durable and flexible, but whose production12 uses fossil fuels and releases pollutants. Each card uses about five grams13 of plastic, and Tailor cites research that 20.5 billion cards will be in circulation by 2025, resulting in nearly 350,000 tons of CO2 being produced. A transaction that doesn’t involve a physical card is part of the solution.

Improvements in hardware and software are one of the most direct ways that payments companies can achieve sustainability goals. But there’s a rich vein of opportunity in leveraging their position in the economy to help others make better decisions. An area that has attracted particular attention is providing consumers with information about the environmental impacts of their purchases and helping them either make better choices or mitigate the impact of emissions.

"With open banking you can get ‘carbon information’ that is linked to the payment being made,” says Nick Maynard, VP of Fintech Market Research at Juniper Research, “and then you can give the user more awareness of the implications of what they’re doing.” Since payments are a common denominator for all economic activity, payment companies are well placed to offer consumers a holistic picture of their carbon impact.

For example, one climate-focused fintech company14 offers a plugin that can be embedded into a bank’s proprietary smartphone app, or a merchant’s online checkout page, to offer customers information about the carbon emissions of what they’re purchasing. The customer is then offered a simple option to pay for an offset. Elsewhere, carbon mitigation is being built into the product directly: one French neobank15 offers a current account which attaches a carbon cost to each purchase and directly makes a donation to a climate-focused conservation project in response.

Naturally, given concerns around greenwashing, best-in-class executions are led by objective research. The Science Based Targets Initiative, for example, provides trusted, informed guidance on approaches to offsetting. There are also payments-specific research projects such as Åland Index, which provides carbon footprint estimations for bank transactions in different categories like food, fashion or travel. This combines high-level data on emissions with a methodology vetted by a leading professional services company. When the Swedish impact fintech Doconomy created an API called the Carbon Calculator for Mastercard, it used the Åland Index. The API looks at the four-digit merchant category codes16 assigned by Mastercard to different merchants depending on what they sell, matches this to the carbon estimates on the Åland Index, then combines this with local adjustment factors to return an estimate for that purchase’s carbon emissions and water use. “The greatest challenge we face in regards to the climate crisis became quite obvious 10 to 15 years ago. But there was a lack of climate literacy: what is the climate crisis? How do I measure the climate crisis? How do I measure my contribution to the crisis?” says Mathias Wikström, founder and CEO of Doconomy. Financial services, he says, needed to alight upon a standardized way of measuring the per-dollar impact of spending on the environment to empower consumers to make the right choices for the planet. If a customer can see the impact of spending $250 in a fast fashion chain, for example, or of buying tickets for a short-haul flight, it makes it real.

There’s a business incentive for financial services to offer this kind of information, Maynard points out: “If you are a bank—and the retail banking market is pretty competitive—if you can show that your solutions can actually enable customers to have a more environmentally friendly approach to their life, that is a differentiator.”

Yet Doconomy isn’t only focused on the consumer. While Mastercard offers its Carbon Calculator product to its client banks, Wikström suggests that some of these banks might not ever incorporate it into their retail banking products. Rather, he says, the calculator can be used to calculate carbon footprints for ESG reporting using bank transaction data. “You can just use it to calculate the carbon intensity score of your complete consumer credit portfolio. So you get an average CO2 emissions impact per euro spent by your retail client.” Legislatures around the world are discussing making this reporting mandatory, Wikström notes, pointing to existing laws in California17 that will require banks to calculate and disclose the carbon emissions tied to their lending. “Over time, I think it’s fair to think that the banks will need to report on this out of a consumer perspective, as well.”

One limitation of current schemes for assessing carbon footprints via payments is the lack of granularity. “If you’re shopping in a supermarket,” says Maynard, “then how do you provide an accurate carbon assessment? It will vary wildly depending on whether you’ve bought bananas from the Caribbean or strawberries from Essex – there’s an element of uncertainty.” The introduction of the new global payments messaging standard ISO 20022 has led some to speculate that a solution may—some day—emerge. This new standard embellishes payment messages with extra metadata fields with drop-down menus of options. “There's going to be a product description field, a country field—you'll have a much better understanding of the data that's there,” says Ciarán Byrne, Head of Global Clearing Product and Transformation within J.P. Morgan Payments. In the future, he posits, it’s possible in theory that sustainability-specific data could be added as a field in itself.

Thomas Verhagen, Senior associate at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), agrees that there is blue-sky potential. But he makes the caveat that even ISO metadata isn’t yet standardized. “ISO doesn’t stipulate the exact data that’s being used. I can see how the [payments] industry, working with neutral outside parties to align on what needs to be communicated and standardized, can lead to a surge of new services and new value-add features, both on the B2C as well as on the B2B side. But you need to come to some kind of definition of what that commons looks like before you and anybody else can draw on it.”

The question of how payments can help drive sustainability is often answered by looking inwards to what the industry itself can do. But there is another axis of opportunity: how payments can help other businesses thrive in ways that could dramatically reduce emissions. In fact, says Attenborough, this may be a more fruitful approach than trying to directly lessen the carbon emissions of payment computation. “The central premise that there would be something directly linked to sustainability, from a payments point of view, is not always a helpful or fertile ground to begin with,” he says.

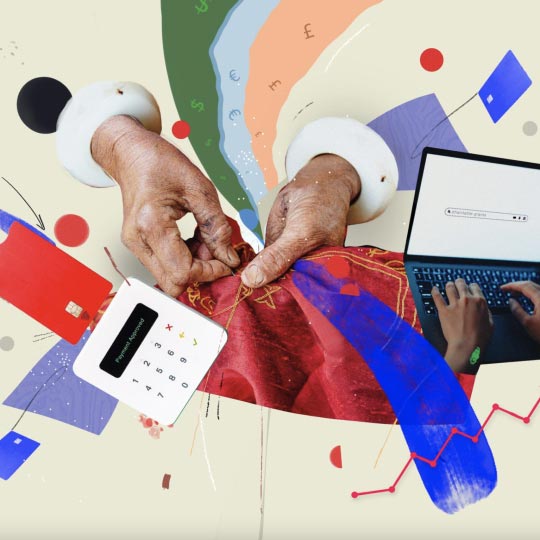

Helping facilitate participation in the circular and sharing economies is one such example. The circular economy is about recycling and reselling, and payments providers can play a number of roles here, whether that’s helping establish trust between buyers and sellers on marketplaces, or enabling seamless, instant pay-outs via novel channels. For example, the Danish city of Aarhus launched a “reverse vending machine” for coffee cups this year; its manufacturer calls it18 the “world's first open managed system for reusable takeaway packaging”. When consumers buy a coffee with an eligible cup, they pay five Danish kroner as a deposit. When they return this cup to one of the machines, they tap their credit or debit card to get this deposit back. The sharing economy—in which individuals reduce their own consumption by using the assets of others—can also benefit from payments innovations. Peer-to-peer payments can make it easier for people to monetize their possessions; Internet of Things payments, in which the machine either requests or executes a payment, can allow objects to autonomously charge for access on a metered, pay-per-use basis.

“Out of everything,” says Verhagen, “I think that the sharing economy and circular economy seem to ‘break parity’: there don’t seem to be many trade-offs that you have to make there, to make quite good savings in terms of the impact on the planet.” But perhaps the biggest immediate opportunity for payments to catalyze cleantech is in transportation.

Mass transit is an area where payments innovation has been shown to have a clear impact on usage. One key recent innovation is the shift from closed- to open-loop ticketing systems. The former is where the transport operator sells tickets or operates a proprietary payment card; the latter is where riders simply tap a credit or debit card to ride. The latter has a range of advantages. It makes the mode of transport easier and faster to use, especially for non-residents or those who may only use it occasionally. It also allows for interoperability between transport systems, whereas closed loop ticketing inevitably produces siloes. Evidence19 shows that the overall consequence is increased ridership.

Although open-loop is becoming increasingly commonplace, it is not yet ubiquitous. But advanced implementations are showing the transformative effect it can have. Consider the Netherlands, which recently became the first country to launch an open-loop, contactless public transport payments system nationwide.20 That means riders can get anywhere in the country with just a tap of their card on departure and another tap on arrival, with the optimal fare calculated on the back-end. No more need to download countless apps. In an open-loop system, payments have a further opportunity to help drive sustainability. Transaction data is a useful proxy for understanding how people use mass transit. One Swedish climate tech company21 processes payments data from client cities’ transit systems and then uses AI to inform them of possible efficiencies that can be found in these systems, helping them to better plan for the transition to net-zero public transport.

The conversation around transport and payments is not only about mass transit. Electric vehicle emissions are between 17 and 30 per cent lower22 than petrol and diesel vehicles, according to a European study. But James Court, Chief Executive of the Electric Vehicle Association of England, notes that around only two percent of cars on British roads are electric vehicles (EVs). In the US, the picture is similar; only 6.8 percent23 of new vehicle sales are EVs. Making these vehicles easy to charge—and by extension, making charging easy to pay for—is key to boosting uptake.

The United Kingdom has taken measures to do just that. Until recently, an EV driver might have needed “18 to 20” different apps to pay for different charging stations, says Court, but from October 2024, all rapid chargers in the United Kingdom have been required by law to accept contactless payments. “A couple of years ago, it was very challenging,” he says. “It was frustrating, especially if you then run into somewhere where you haven’t got phone signal and you need an app.”

Although it hardly sounds innovative, equipping chargers with the means to quickly accept a range of different payment types requires collaboration between multiple organizations, and is a shift that still needs to happen in many countries. “This is one area where the UK has definitely made some huge improvements, and other countries are seeing what we’ve managed to achieve.”

As EV charging becomes associated with a seamless customer experience, it is giving rise to ecosystems of businesses that differentiate on convenience of payment. At London’s Gatwick Airport, for instance, one EV company24 has launched an “electric forecourt”, featuring 30 charge points and an integrated refreshment shop on site that uses autonomous grab-and-go payments technology. The customer taps a payment card upon entry and then takes what they want from the shelves; cameras in the shop track the customers’ purchases and then charge them retroactively. Proof, if ever, that the future is here, just unevenly distributed.

Payments has always been an industry focused on scale. With billions of transactions taking place each year around the world, even the smallest new efficiencies can have a considerable impact.

Among the experts WIRED spoke to, there was a clear theme that now is the moment for the industry to realize its potential for enacting change. The broad trends were clear: the payments sector has an opportunity to reduce its own emissions, help consumers better understand theirs, and can function as a catalyst for structural shifts in the economy that can aid decarbonization.

There were a range of opinions, however, as to where emphasis should be placed. Verhagen, for example, wants to see more efforts to measure payments’ impact on water security and biodiversity, not just carbon emissions; Attenborough drives home the importance of changing consumer behaviors through payment technology. Others placed importance on open banking, transparency and better communication between financial institutions.

But all of them recognized the importance of a multi-faceted approach in the drive for net zero. And financial services companies are keen to prove they are winning the race to get there, says Wikstrom. “From a market driver’s perspective, if we can make it profitable to win, then saving the planet will be done in no time—because it’s profitable.”

ILLUSTRATION: Tom Peake