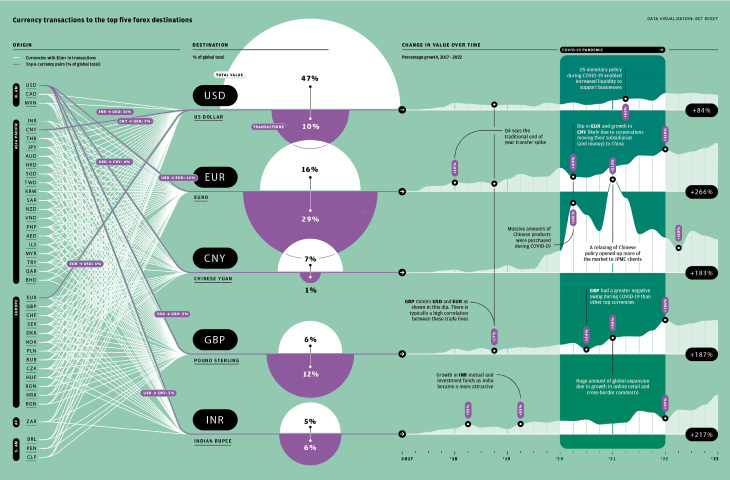

Can carbon removal help solve the climate crisis?

Above: Climework’s Orca facility in Iceland.

The promise of direct air capture is huge—but scaling it is challenging

REALITY CHECK

We all know what needs to happen to mitigate the climate crisis. Keeping global heating to within 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels will require industries, individuals, and nations to work together to achieve global net zero by 2050. But to get there, simply cutting back won’t be enough. Carbon will need to be actively removed from the atmosphere—at least 10 billion tons1 per year by 2050, according to estimates.

This has spurred a surge of interest in carbon removal technologies. Many of these take the form of an add-on to carbon-intensive industries. They trap emissions as they’re released from an industrial facility, such as a power plant or cement factory, and the carbon is then stored, often by burying it deep underground. Another, more emergent category, however, has particularly caught imaginations: Direct air capture (DAC). This involves pulling carbon from the ambient atmosphere, meaning it can remove carbon that has already been emitted by vehicles, households or industrial processes. It has piqued the interest not only of governments, but businesses who wish to offer climate-related products—payments companies included.

A number of start-ups are proving the concept of DAC. Take Climeworks, a Swiss company founded in 2009. Its Orca facility is the largest direct air capture plant in the world. Opened in Iceland in 2021, the plant can suck 4,000 tons of carbon dioxide straight out of the atmosphere every year—equivalent to the emissions generated by around 500 American homes. The technology works by running the air through specialized filters to capture carbon so it can be stored underground. And money is duly flowing into the sector: investment in DAC hit a record of $6.4 billion in 20222. Yet there are challenges to solve for it to begin neutralizing emissions to a meaningful degree.

“We know we can do it,” says Dr. Emily Grubert, a professor of sustainable energy policy at the University of Notre Dame. “But I don’t think people have really fully thought through the implications of how difficult it would be to do that relative to mitigation.”

Beyond technical challenges around efficiency, there are practical ones. Companies and governments need to figure out where to store the carbon that’s captured—and some communities have resisted3 it coming to their neighborhoods. “They just really don’t want to be dumping grounds,” says Grubert. “This is effectively waste.”

There are also economic challenges, complicated by the fact that to fund carbon capture, DAC companies need to be able to sell carbon credits. This means they currently have to rely on a market that is fragmented and opaque.

At their most simple, carbon credits are contracts for the removal or neutralization of a ton of carbon. One of the most common mechanisms involves simply paying for conservation efforts in tropical rainforests, or for reforestation of degraded areas. But the market has struggled with the challenges of verifying and pricing carbon, as well as with scandals4 over mislabeling and accounting of offsets. For the market to work—and therefore further support DAC expansion—these credits need to be traceable, verifiable and transparent.

“Guardrails are needed to make sure that what we’re measuring and reporting and verifying to then be used as carbon credits is a very robust process,” says Dr. Ankita Gangotra, an associate at the World Resources Institute who is researching avenues to decarbonize the industrial sector.

Yet within this challenge also lies an opportunity for DAC. One of the appeals of carbon removal tools like direct air capture is that their results are not theoretical: They are measurable, and hence easier to account for. That’s important—customers, whether they’re big businesses or consumers, need to feel sure that the credit they’re paying for represents a genuine mitigation.

The payments industry has become increasingly interested in higher-technology carbon removal because it already engages with the credits marketplace. Some have developed tools to make buying carbon credits easier for consumers. Several payments businesses have integrated emissions trackers into their products5, allowing customers to see the emissions associated with their purchases, and to buy offsets.

Bringing carbon reduces close to the consumer at the point where they’re making a transaction doesn’t just help them make a more informed decision. It also has the side benefit of expanding access to carbon credits, deepening and securing the market—which contributes to improving the carbon credits ecosystem on which the success of DAC partly depends.

Against this backdrop, Climeworks, for example, has signed deals for carbon credits with major companies. Climeworks is about to unveil Mammoth, its second facility in Iceland, which will have a nameplate removal capacity of up to 36,000 tons per year. By 2050, the company wants to be able to sequester a gigaton of carbon annually, according to Ann-Kristin Koch, Climeworks’ chief communications officer.

The promise of technology like this has spurred governments around the world to help solve the associated challenges. The United States plans to invest at least $3.5 billion6 in carbon capture and storage technologies. But it’s important to keep that in perspective. It’s a huge sum, but still a long way off what the country needs to meet its climate goals.

Today, the U.S. has the means to capture 20 million tons of carbon a year; that’s only between one and five percent of what’s needed by 20507. Even those who are working to develop and popularize these innovations admit that they’re not a silver bullet—merely part of the suite of things that need to be done to prevent a climate catastrophe.

“Our technology alone will not be sufficient to mitigate climate change,” Climeworks’ Koch says. “We need to do everything we can to reduce emissions.”

SOURCES: AS PER WIRED, MAY 2024

IMAGES: CLIMEWORKS. PRESS ASSETS MAY 2024, GETTY/ WALAIPORN SANGKEAW

icon

Loading...